Colonial commodity sugar:

Flensburg's global entanglements

What has Flensburg to do with colonialism? In the following, we would like to tell a story that illustrates Flensburg's global entanglements, using the colonial commodity sugar as an example, and thus provide an overview of Flensburg's colonial history. We, Nelo Schmalen and Lara Wörner, wrote a large part of this story as part of the Network Flensburg Postcolonial for the Decolonial [Hi]stories section of the Decolonial Memory Culture in the City project. There you can also find the story on an interactive map, where the different geographical locations of the story are marked. The story here is complemented by some references to further materials and other contributions on this website.

Flensburg's global entanglements

Today, Flensburg is often marketed as the ‘city of sugar and rum’. Sugar and the by-product of sugar production, cane rum, were made from sugar cane – cultivated mainly in the Caribbean – until sugar beet was grown in Europe. As Flensburg was the third largest port in the Danish state until 1864, the city benefited from favourable trading conditions with the Danish colonies in the Caribbean, now known as St Thomas, St Croix and St John (US Virgin Islands). Sugar production was closely linked to the transatlantic slave trade and the plantation economy. After Flensburg’s membership of the Danish state ended in 1864, the city became part of Prussian/German colonialism. Changes in tax laws made trade with Danish colonies in the Caribbean more difficult. As a result, the cane rum for Flensburg’s rum production was from then on mainly imported from the British colony of Jamaica.

This article focuses on Flensburg’s entanglements during its time as part of the Danish state. The colonial relationships between Osu-Castle in Ghana, the plantation economy of St Croix in the Caribbean and the city of Flensburg are illustrated by means of the colonial commodity sugar. In all three places, the history of exploitation has left its mark on urban structures and landscapes. If you want to take a closer look at the places and their connections, you can browse through the article on Dekoloniale.

The extent to which Flensburg merchants were involved in and benefited from trade is exemplified by the Christiansen family. The romanticised self-image of “capable merchants and sailors” often presents a one-sided narrative. It overlooks the fact that the unpaid labour of enslaved people in the Caribbean was a cornerstone of the merchants’ prosperity in Flensburg.

Colonial gardens

A starting point for our look at Flensburg’s colonial connections is Christiansen Park. The park was laid out before 1800 and later greatly expanded. Who developed this park and where did the wealth come from that made the expansion of the gardens possible?

The answer to this question leads us to the colonial commodity of sugar, which was particularly important for Flensburg. Sugar was imported from the three Danish colonies in the Caribbean, now known as St. Thomas, St. Croix and St. John (US Virgin Islands). Flensburg merchants traded unequal trade with the three islands for 109 years (from 1755 to 1864) and profited particularly from the trade in cane sugar. The prominent Flensburg merchant family Christiansen also made large profits from this business, investing in prestigious facades and elaborate gardens to demonstrate their wealth.

Part of the historic Christiansen Park is now built on, but the rest of the park area has been in municipal ownership since 1992 and is used by many Flensburg residents. In 2023, Christiansen Park was renovated alongside two other green spaces, with the aim of making the park “bring the park back to life as a unique cultural-historical ensemble […].” In cooperation with post-colonial initiatives, academics and the heritage protection authority, the city had a plaque erected that reminds us how the creation of the park was linked to the exploitation of enslaved people on Caribbean sugar cane plantations.

Quotes:

Stadt Flensburg: Flensburger Landschaftsgärten (Christiansens Gärten), 2023. https://www.flensburg.de/Startseite/Projekt-Christiansens-G%C3%A4rten.php?object=tx,2306.5&ModID=7&FID=2306.9037.1 (zuletzt abgerufen 08.07.2024).

References:

Bauriedl, Sybille / Wörner, Lara / Carstensen-Egwuom, Inken / Schmalen, Nelo: Christiansenpark – Ein Garten der Kolonialzeit, Netzwerk Flensburg Postkolonial, 2023. URL: https://flensburg-postkolonial.de/christiansenpark/ (zuletzt abgerufen 8.7.2024)

Redlefsen, Ellen: Die Kunsttätigkeit der Flensburger Kaufleute Andreas Christiansen sen. und jun. und die Spiegelgrotte, in: Nordelbingen 33, 1964, S. 13-44.

A more detailed text on the colonial references of Christiansenpark is available on this website. It was published in summer 2023, after the renovation of the area has been completed. The text takes a closer look at the Flensburg merchant family Christiansen, the creation of the gardens and the simultaneity of Enlightenment ideals in landscape gardens and colonial violence on the plantations.

In total, more than 12 million Africans were deported across the Atlantic to the Americas. The Slave Voyages website makes the records of enslavement and deportation accessible. The website includes visualisations of the routes of the transatlantic slave trade, various databases, educational materials and images. The site is available in English, Spanish and Portuguese only.

Enslavement and deportation

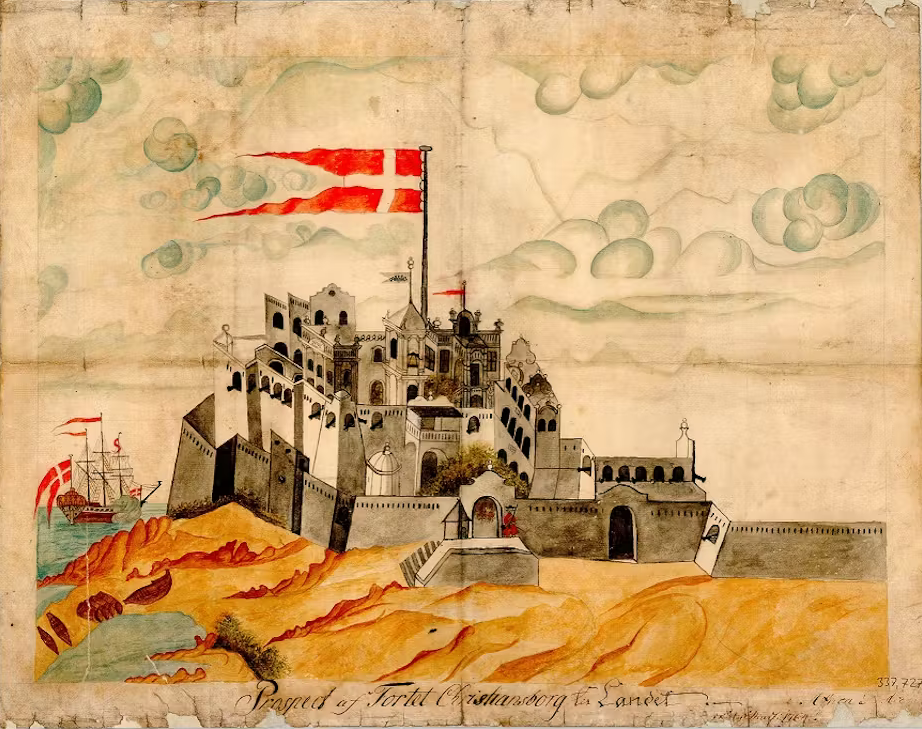

The Christiansen family’s wealth dates back to the 17th century on the coast of West Africa. At that time, European companies built fortresses and smaller bases along the entire West African coast. Africans captured inland were held in these forts for months before being deported across the Atlantic. Denmark-Norway also constructed the Christiansborg Fortress, now known as Osu Castle, in present-day Accra from 1661. In addition to the trade in ivory and gold, the fortress served as the seat of the Danish colonial administration, which coordinated and organised part of the transatlantic slave trade in collaboration with indigenous rulers.

Various (partly) private trading companies were involved in the transatlantic slave trade under the Danish flag. The Danish state repeatedly granted these companies royal privileges in trade and assumed control of operation when the companies went bankrupt.

It is estimated that over 100,000 Africans from West Africa were deported under the Danish flag through the ‘Gate of No Return’. The crossing took two to three months and even on the ships, people often resisted by committing suicide, going on hunger strikes, or organising mutinies. Of the more than 100,000 Africans abducted, around 85,000 survived the journey and reached the Caribbean alive. Upon arrival, the survivors were sold at so-called slave markets on St. Thomas and other locations.

The dehumanisation, abduction and violent exploitation of these people’s labour were central to sugar production in the Caribbean plantation economy.

References:

Emory Centre for Digital Scholarship: SlaveVoyages. Explore the Dispersal of Enslaved Africans Across the Atlantic World, 2010. URL: https://www.slavevoyages.org/ (zuletzt abgerufen 28.7.2024)

Petersen, Marco L.: Einleitung. Das (post-)koloniale Sønderjylland-Schleswig, in: Petersen, Marco L. (Hrsg.): Sønderjylland-Schleswig kolonial. Das kulturelle Erbe des Kolonialismus in der Region zwischen Eider und Königsau, 2018, S. 29–46.

Plantation economy

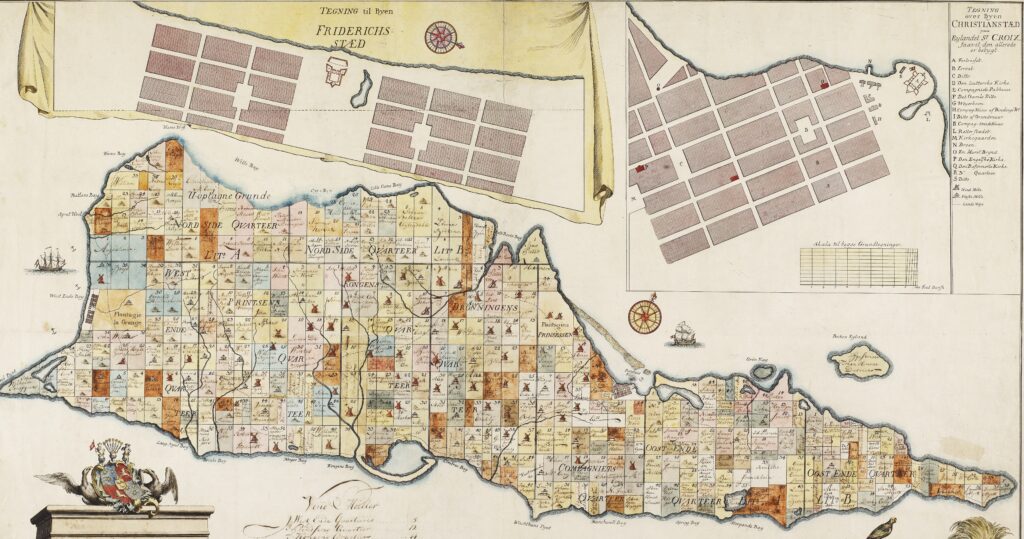

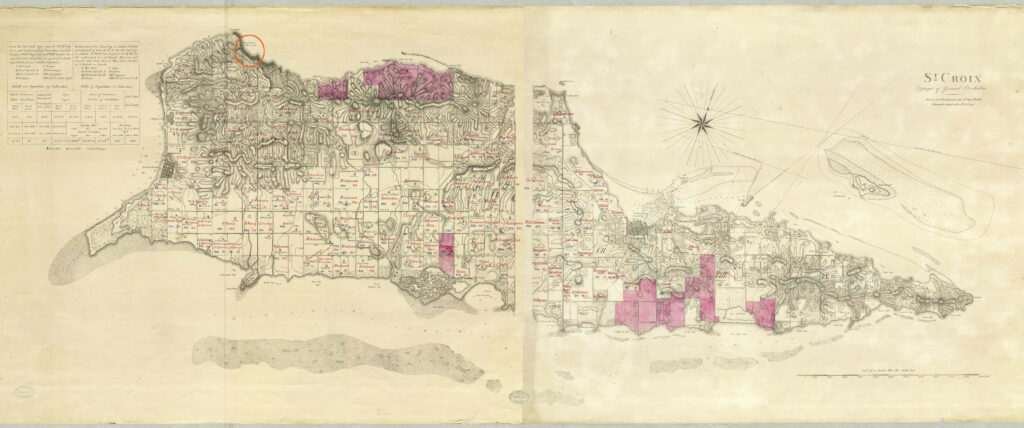

The majority of the abducted Africans were sold to plantation owners in the Caribbean. After France “sold” the island St. Croix to the Danish West India Company in 1733, Danish trading companies established a system of plantation farming. By 1754, almost all of the island’s mahogany forests had been cut, and the land was divided into plantations.

The land was stolen from the Indigenous population, the Taíno/Arawak. Their expropriation, expulsion and death – whether through violence or disease – had already been carried out by various European colonial powers before Danish colonial rule. Under Danish colonial rule in 1754, there were approximately 300 plantations on St. Croix, ranging in size from 20 to 283 hectares. This corresponds to an area of 28 to 396 football fields per plantation.

The term “plantation” refers to the spatially defined area where agricultural products are cultivated and processed in monocultures. At the same time, the term “plantation economy” describes a system of agricultural mass production for the global market. This system was (and often remains) dependent on the violent expropriation of land from Indigenous populations, the destructive exploitation of nature, and a racist, global division of labour.

Historically, within this division of labour, Black people were dehumanised and devalued as commodities. Enslaved people died on the sugar cane plantations due to poor nutrition and hygiene, overwork, and accidents. As few children were born and many died young, this system was dependent on the constant deportation of people. Although slavery was abolished on St. Croix as a result of the rebellion of enslaved people in 1848, the plantations continued to operate with so-called indentured labour: Initially, however, little changed for the workers. Later, workers from India were forced into contract labour on the plantations.

References:

Ferdinand, Malcom: Decolonial ecology. Thinking from the Caribbean world, 2021. Link: https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2022.2160115

Gøbel, Erik: The Danish Slave Trade and Its Abolition, 2016.

Roopnarine, Lomarsh: Maroon Resistance and Settlement on Danish St. Croix, in: Journal of Third World Studies 27, 2010. Link: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45194712

Rigarkivet. The Danish West-Indies – Sources of History: The population trend in the Danish West Indies, 1672-1917. https://www.virgin-islands-history.org/en/history/personal-history/the-population-trend-in-the-danish-west-indies-1672-1917/ (zuletzt aufgerufen

21.10.2024).

The Museum Vestsjælland has compiled educational material that gives an overview of the Danish plantation economy in the Caribbean and Danish-Caribbean history. As a former Danish town, Flensburg also has a large part to play in this history. The material includes tasks and discussion questions for students. The material is only available in English and Danish and, according to the museum, is aimed at young people in grades 7-10.

The anthology 'Denmark as a Global Player 17th-20th Century - Colonial possessions and historical responsibility' gives an overview of Denmark's time as an imperial power. The anthology includes information on the structures and major players in Danish colonialism, as well as specific studies of Denmark's colonial possessions in the North Atlantic, India, Ghana and the American Virgin Islands.

Fireburn was the name given to an uprising of plantation workers in the Danish colony of St Croix in 1878. the Fireburn Files archive provides access to documents from the Danish colonial administration relating to this uprising.

In her exhibition 'Luisa Ascending', Felisha Carénage explores the story of 14-year-old Luisa Calderón, who lived in Trinidad in the Caribbean in the early 19th century. The exhibition explores how violence in the colonies relates to our reality in the here and now. The brochure developed as part of the exhibition provides an insight into possible answers and the connection with Flensburg's involvement in Danish, German and British colonialism.

Resistance and survival

The plantations were not only sites of violence and exploitation but also places of survival and resistance. Particularly on the so-called “plots” or “provision grounds” – areas where enslaved people grew their own food – they managed to create spaces of autonomy and preserve cultural practices.

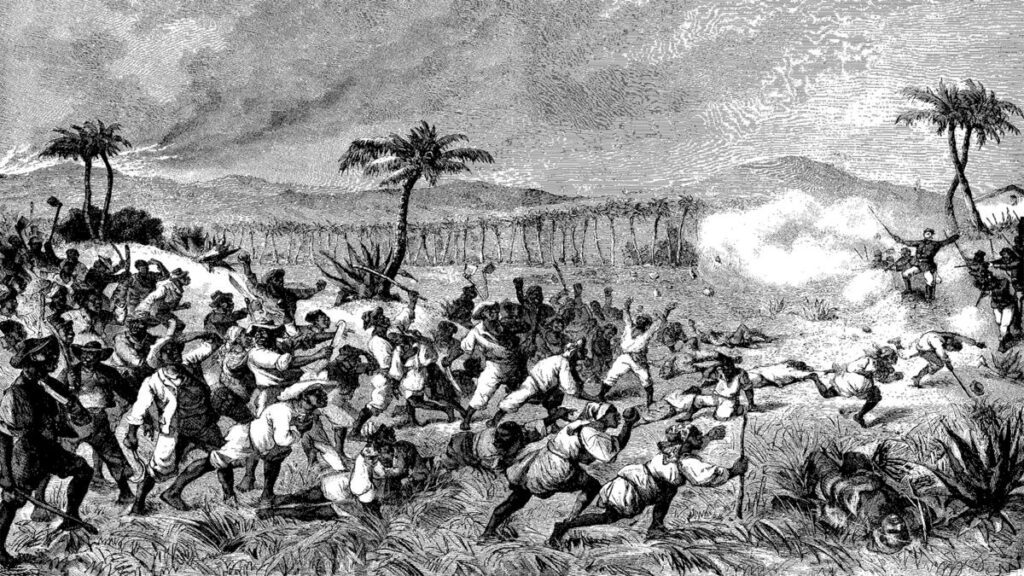

Rebellions occured frequently: As early as 1733, enslaved people on the island of St. John successfully took control of the island for several months. In 1759, William Davis was accused of planning a rebellion on St. Croix and was tortured as a deterrent. Brutal punishments and torture instruments, such as the neck iron, demonstrate the ubiquity of resistance, which constantly jeopardised the rule of the colonisers. After a revolt in 1848 on St. Croix, during which rebels nearly took control of Frederiksted, the local governor-general hastily declared an end to slavery, leading to its abolition in the Danish Caribbean colonies.

However, even after 1848, Black workers were subjected to severe restrictions on their freedom through oppressive labour laws and harsh working conditions. On October 1, 1878 – the only day of the year workers were allowed to change jobs – four women, Mary Thomas, Mathilda MacBean, Agnes Salomon and Susanna Abramson, led a rebellion against this oppression. They set fire to nearly 350 hectares of sugar cane fields and parts of Frederiksted, forcing some plantation owners to flee. This uprising became known as “Fireburn.”

References:

Sebro, Louise: The 1733 Slave Revolt on the Island of St. John: Continuity and Change from Africa to the Americas, in: Magdalena Naum / Jonas Monié Nordin (Ed.): Scandinavian colonialism and the rise of modernity. Small time agents in a global arena, 2013, pp. 261-274.

Belle, La Vaughn: We are the monuments that won’t fall, Keyword ECHOS, 2020.

Link: https://keywordsechoes.com/la-vaughn-belle-the-monuments-that-wont-fall (zuletzt abgerufen 7.10.2024).

Fireburn Files. The collection – work in progress. Link: https://fireburnfiles.dk/ (zuletzt abgerufen 7.10.2024)

Dixon, Euell A.: The Fireburn Labor Riot, Virgin Islands (1878), BLACKPAST, 12.9.2020. Link: https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/the-fireburn-labor-riot-united-states-virgin-islands-1878/ (zuletzt abgerufen 7.10.2024).

Rigarkivet. The Danish West-Indies – Sources of History: The slave rebellion on St. Croix and Emancipation. Link: https://www.virgin-islands-history.org/en/timeline/the-slave-rebellion-on-st-croix-and-emancipation/ (zuletzt abgerufen 7.10.2024)

Tafari-Ama, Imani: Rum, Schweiß und Tränen. Flensburgs Kolonialgeschichte und Erbe, in: Grenzfriedenshefte. 64, 85–104, 2017. Link: https://www.dein-ads.de/fileadmin/download/pdf_grenzfriedenshefte/2017/gfh_jb2017-min.pdf (zuletzt abgerufen 7.10.2024)

Remembering the Resistance

After the suppression of the Fireburn Uprising, over 400 participants were captured by the Danes. Some of the leaders, particularly the men, were executed immediately. However, the four female leaders, Queen Mary, Queen Agnes, Queen Mathilde and Queen Susanna, were convicted and had to serve part of their sentences in Copenhagen.

While the Fireburn is vividly remembered on the formerly Danish-colonized islands – for example, through the memorial The Three Rebel Queens of the Virgin Islands in Charlotte Amalie on St. Thomas or through annual commemorations on 1 October – the four women were long unknown in Denmark. As is so often the case, the people who resisted colonial rule were made invisible.

The transnational work of artists La Vaughn Belle from the US Virgin Islands and Jeannette Ehlers from Denmark counters this erasure. Together, they created the monumental public artwork “I am Queen Mary”, which was unveiled in front of the former West Indian Warehouse in Copenhagen in 2018. Queen Mary sits on a wicker chair with a torch and a machete on a plinth made of washed coral stone from St Croix.

The monument is the first monument in Denmark to honour a Black woman. After storm damage in 2020, only the plinth remains. While the fundraising campaign for a permanent bronze sculpture is underway, the sculpture can be viewed with augmented reality since May 2024.

References:

Belle, La Vaughn /Ehlers, Jeannette: I am Queen Mary, https://www.iamqueenmary.com/ (zuletzt abgerufen 11.7.2024)

Bauriedl, Sybille / Carstensen-Egwuom, Inken: Perspektiven auf Geographien der Kolonialität, in: dies. (Hrsg.): Geographien der Kolonialität, 2023.

The „I am Queen Mary“ monument in Copenhagen 2018 honors the resistance fighters. © Sarah Giersing

Decolonial memory culture and politics in other places, critical exhibitions in museums and other postcolonial initiatives also inspire our work as the Network Flensburg Postcolonial. That's why we have collected some things in our blog.

The Danish National Archives has collected many records of Danish colonial rule in the US Virgin Islands. Here you will find descriptions, registers, letters, maps and illustrations of life and exploitation on the colonised islands.

Flensburg merchants on St. Croix

The profiteers of the sugar trade must have been aware of the exploitation and violence in the Danish colonies. The Flensburg merchant Andreas Christiansen Sr (1743-1811) himself travelled to St. Croix several times for up to nine months to establish trade relations in the interests of Flensburg merchants. His son, Andreas Christiansen Jr (1780-1831), also benefited from these connections, using the profits to finance the expansion of the garden around 1800.

When Christiansen Sr first stayed on St. Croix in 1767, the island was already almost completely deforested. The majority of the population were enslaved Africans, alongside a small number of Europeans who supervised the labour as plantation owners.

By the end of the 1790s, the number of enslaved people on St. Croix had risen steadily: by 1797, there were over 25,000 enslaved people living there. In contrast, the number of Europeans on St. Croix was only around 2,200. These figures show the rapid expansion of the plantation economy on the island and indicate how much profit Danish companies derived from sugar cane cultivation. Additionally, around 1,100 free black people were living on the plantations and in the towns.

Less documented were “Maroons” – Black people who escaped the plantation system by freeing themselves and fleeing. On St. Croix, maroons primarily lived in the northwest, in the island’s few and difficult-to-access forests (today’s David Bay), where they formed maroon communities. However, they could not live completely independently of the rest of society on St. Croix and had to come into contact with enslaved people repeatedly in order to provide for themselves. They also used the geographically favourable location to escape from here to Puerto Rico.

References:

Albrecht, Ulrike: Flensburg und die Christiansens. Kaufleute Reeder und Unternehmer in der Frühindustrialisierung, in: Gesellschaft für Schleswig-Holsteinische Geschichte (120), 1995, S. 113–127.

Grigull, Susanne: Kolonialmöbel. Ein Beitrag Flensburgs zur Entwicklung eines Möbelstils, in: Petersen, Marco L. (Hrsg.): Sønderjylland-Schleswig kolonial. Das kulturelle Erbe des Kolonialismus in der Region zwischen Eider und Königsau. Odense, 2018, S. 177-193.

Black History Month 2024: Taíno. Indigenous Caribbeans, 2024. Link: https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/pre-colonial-history/taino-indigenous-caribbeans/https:/www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/pre-colonial-history/taino-indigenous-caribbeans/ (zuletzt abgerufen 8.7.2024)

Rigarkivet: The Danish West-Indies – Sources of History. The population trend in the Danish West Indies, 1672-1917. Link: https://www.virgin-islands-history.org/en/history/personal-history/the-population-trend-in-the-danish-west-indies-1672-1917/ (zuletzt abgerufen 8.7.2024)

Roopnarine, Lomarsh: Maroon Resistance and Settlement on Danish St. Croix, in: Journal of Third World Studies 27, 2010, S. 89-108. Link: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45194712

Christiansen, Andreas, Autobiographie, 1807, Stadtarchiv Flensburg XII Hs 01515 Bd3001-6.

Dunnavant, Justin P./Wernke, Steven A./Kohut, Lauren E. (2023): »Counter-Mapping Maroon Cartographies:. GIS and Anticolonial Modeling in St. Croix«. 22(5), in: ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 22, S. 1294-1319. Link: https://doi.org/10.14288/acme.v22i5.2262

Profiteers of the sugar trade

One of the main profiteers of the colonial goods trade in Flensburg was Andreas Christiansen Sr. From 1778, the Christiansen ran the city’s most important sugar refinery, which primarily processed raw sugar from St. Croix. Between 1783 and 1792, Christiansen Sr more than doubled his fortune. The trading family profited from the colonial commodity sugar in several ways: through transportation as shipowners, through refining as sugar refinery operators, and through sales as merchants.

Trade with plantation owners in the Caribbean led to a significant increase in shipbuilding in Flensburg. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Christiansens owned the “St. Croix”, the largest ship to sail from Flensburg to the Caribbean. There, the Christiansens and other Flensburg merchants purchased goods, in addition to raw sugar, rum, tobacco, coffee, rice, and mahogany wood, and shipped them to Flensburg on their own ships and processed and sold them there.

These trade relations were a central component of the transatlantic enslavement trade, which consisted not only the deportation of millions of people from Africa to the Caribbean and the Americas but also of the shipment of colonial raw materials from the colonies to Europe and the sale of goods processed in Europe in the colonies. The unpaid labour of the enslaved people and the exploitation of natural resources on the Caribbean islands were the foundation of the profits enjoyed by Flensburg merchants within these trade networks.

References:

Albrecht, Ulrike: Flensburg und die Christiansens. Kaufleute, Reeder und Unternehmer in der Frühindustrialisierung, in: Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Schleswig-Holsteinische Geschichte 120, 1995, S. 113-128.

Gesellschaft für Flensburger Stadtgeschichte (Hrsg.): Flensburg. Geschichte einer Grenzstadt, Neustadt an der Aisch, 1966.

An oil painting of Andreas Christiansen sen. by N. Peters H. S. "Successful" merchants in Flensburg were honoured with portraits like this one. The violent exploitation behind the success remains invisible. © Flensburger Schifffahrtsmuseum, CC BY-NC-SA Lizenz

Maps can be used to draw attention to the traces of colonialism in public space, and thus make visible a counter-narrative to Eurocentric colonial history. Maps are powerful tools that communicate the cartographer's worldview. Decolonial and critical mapping re-appropriates this tool and aims to challenge dominant worldviews and supplement them with suppressed histories. On our blog you will find several posts on decolonial and critical maps.

Urban structures through colonial profits

The profitable trade in and equally profitable processing of sugar and other colonial goods characterises Flensburg’s urban structures today.

As early as 1783, A. Christiansen Sr processed as much sugar in his sugar refinery as five other Flensburg refineries combined. In 1789, he had the so-called “West India Warehouse” built as a storage facility and trading house for sugar and other colonial goods. The goods were stored here until further processing or sale. In 1981, the warehouse was renovated and converted into apartments. The remains of the gable crane, still visible today, indicate the building’s former colonial function as a warehouse for goods such as raw sugar, cane rum in heavy oak barrels, tobacco, cocoa, tea, and spices.

In 1833, 1,400 tons of Caribbean raw sugar arrived in Flensburg. Converted into today’s shipping containers, this equates to 49 containers – in other words, a container of sugar almost every week. This raw sugar was processed not only in Flensburg’s sugar refineries but also in refineries throughout the duchy. The sugar was refined by repeated melting and boiling, resulting in different types of sugar such as fine refined sugar, rock candy, and sugar syrup. Sugar production in Flensburg reached its peak in 1846: In this year, 928 tons of sugar, 257 tons of syrup, and 287 tons of rock candy were produced in Flensburg by over 60 employees.

The economic upturn and the profits from the trade in colonial goods also impacted the town’s structure. Additional buildings for the manufacturing industry and warehouses for storage were constructed in the existing, very narrow merchants’ courtyards. The present-day charm of the beautiful, compact merchants’ courtyards, which offer space for cozy cafés, apartments, or stores, shielded from the busy harbor promenade on one side and the pedestrian zone on the other, is therefore also a result of Flensburg’s economic upswing during the colonial era.

References:

Albrecht, Ulrike: Das Gewerbe Flensburgs von 1770 bis 1870. Eine wirtschaftsgeschichtliche Untersuchung auf der Grundlage von Fabrikberichten, 1993.

Galloway, J. H.: The sugar cane industry. An historical geography from its origins to 1914 (= Cambridge Studies in historical geography, Band 12), 1989.

Schmalen, Nelo A.: Kolonialität der urbanen Transformation am Hafen-Ost in Flensburg. Eine raumhistorische Untersuchung zum Umgang mit den kolonialen Strukturen im Stadtraum, 2023. Link: https://www.uni-flensburg.de/fileadmin/content/abteilungen/geographie/poe-euf/2023-wp1-schmalen.pdf (zuletzt aufgerufen am 08.07.2024).

Sand and Bricks: Traces of the Caribbean Crossings

The sugar and profits that came to Flensburg left their mark not only on the city structures but also on the landscape and the harbour structure. To make the sailing ships seaworthy for the Atlantic crossing, they needed ballast in their hulls. On the way to Flensburg, the ships were usually heavy enough due to imported raw sugar and rum. However, on the way to the Caribbean, the ships transported supplies from the region for the plantations, such as processed foods, building materials, and linen fabrics. These were sold locally to the white population. To make the ships heavy enough, they also loaded sand and later bricks into the hulls as ballast.

Loading took place at the ballast bridge in the east harbour, opposite the old town. The path from the ballast bridge led between two houses built in 1744 and still preserved today to the ballast mountain. Sand was mined here as ballast and for brick production. There was also a brickworks at the east harbour. The buildings, changes of the banks, and mining of materials for the ballast are still visible today in the area at the east harbour and the public park. Street names such as Ballastberg, Ballastkai and Ziegeleistraße also refer to this infrastructure.

Flensburg bricks also shape the image of the old town in Charlotte Amalie on St. Thoma, such as in the 99 steps that still connect the city center with the Skytsborg watchtower built by the Danes in 1679.

References:

Schmalen, Nelo A.: Kolonialität der urbanen Transformation am Hafen-Ost in Flensburg. Eine raumhistorische Untersuchung zum Umgang mit den kolonialen Strukturen im Stadtraum, 2023. https://www.uni-flensburg.de/fileadmin/content/abteilungen/geographie/poe-euf/2023-wp1-schmalen.pdf (zuletzt aufgerufen am 08.07.2024).

Overdick, Thomas: Kontaktzonen, Dritte Räume und empathische Orte: Zur gesellschaftlichen Verantwortung von Museen, in: Hamburger Journal für Kulturanthropologie (10), 2018, S. 51– 65.

How did the waterfront, the terrain and the settlement structure at the port of Flensburg change in the course of Flensburg's colonial entanglements? Using a comparative map analysis and four (or five) different historical phases, Schmalen identifies the material infrastructures that were created for profit in Flensburg during the colonial period and the traces of which are still visible today. The website also contains a more detailed text explaining the different shorelines.

Colonialism and the associated transatlantic slave trade and racialised system of enslavement have caused some of the most horrific crimes against humanity. The demand for restitution and compensation for these crimes is a central element of reparative justice. CARICOM is an association of Caribbean states. The Caribbean Reparations Commission, established within CARICOM in 2013, has developed a 10-point plan of reparations demands. The website also provides more information on the background to the reparative justice debate.

Exhibition Rum, Sweat and Tears by Dr. Tafari-Ama

Sugar still plays an important role in Flensburg’s historical narrative today. Flensburg’s involvement in Danish colonialism and its subsequent relationships with the British Empire, without which Flensburg’s “German Flavoured Rum” from Jamaica would not exist, are remembered today primarily in a romanticised way, framed as heroic stories. The memories of the Christiansen family as “extraordinarily successful merchants, shipowners, and entrepreneurs” are just as one-sided as Flensburg’s self-image as a “sugar and rum town”. However, these narratives are only complete when considered alongside a remembrance of colonial violence and present-day injustices.

In 2017, the special exhibition “Rum, Sweat and Tears”, curated by Dr. Tafari-Ama, countered this one-sided memory. The exhibition was initiated and shown by the Flensburg Maritime Museum in 2018 to mark the 100th anniversary of the sale of the former Danish islands to the USA.

In two exhibition rooms, the exhibition explored Flensburg’s trade with the Danish colonies, plantation work, and enslavement, as well as resistance from an African-Caribbean perspective. During the 18 month of research for the exhibition, Tafari-Ama recorded over 150 mini-interviews in the US Virgin Islands, Ghana, and Flensburg, which became part of the exhibition.

The exhibition required visitors to actively engage with colonial violence by focusing on the ongoing psychological impacts of colonization, which for the descendants of enslaved people includes the partial loss of their African identity. People of African descent were portrayed here as resistant subjects who broke the power of the colonizers through self-assertion and survival, not merely as victims of dehumanization and violence.

Quotes:

Philipsen, Bernd: Andreas Christiansen – Unternehmer und Mäzen, in: shz, 25.08.2009 (zuletzt abgerufen 27.9.2024). Link: href=”https://www.shz.de/lokales/flensburg/artikel/andreas-christiansen-unternehmer-und-maezen-40979412

References:

Tafari Ama, Imani: Ontology of Objects, Beitrag bei der „What’s Missing? Collecting and Exhibiting Europe“ – Konferenz, 2009.

Tafari-Ama, Imani: „An African Carribean Perspective on Flensburg’s Colonial Heritage“, in: Kult 16, S. 7-30, 2020.

Flensburger Schifffahrtsmuseum: Einblicke in das Konzept der Sonderausstellung “Rum, Schweiß und Tränen” (zuletzt abgerufen 7.10.2024). Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Emy_1J7zAg

Overdick, Thomas: Kontaktzonen, Dritte Räume und empathische Orte: Zur gesellschaftlichen Verantwortung von Museen, in: Hamburger Journal für Kulturanthropologie (10), 2019, 51– 65.