Mapping as a method of decolonial memory practice in European cities

A large number of postcolonial initiatives use maps to draw attention to the traces of colonialism in public spaces in their respective cities, thus making visible a counter-narrative to Eurocentric colonial histories. The maps typically record buildings, infrastructure, monuments and the names of streets, squares or parks as physical sites of remembrance. In an article published in 2024 in the journal sub\urban (German only), Sybille Bauriedl (European University Flensburg) and Linda Pasch (University of Bonn) look at postcolonial maps. The article examines the extent to which the maps combine decolonial politics of memory with a critical reflection on map production and the power of maps. The article presents and analyses 35 postcolonial maps in the form of a table. The authors classify the maps into three types:

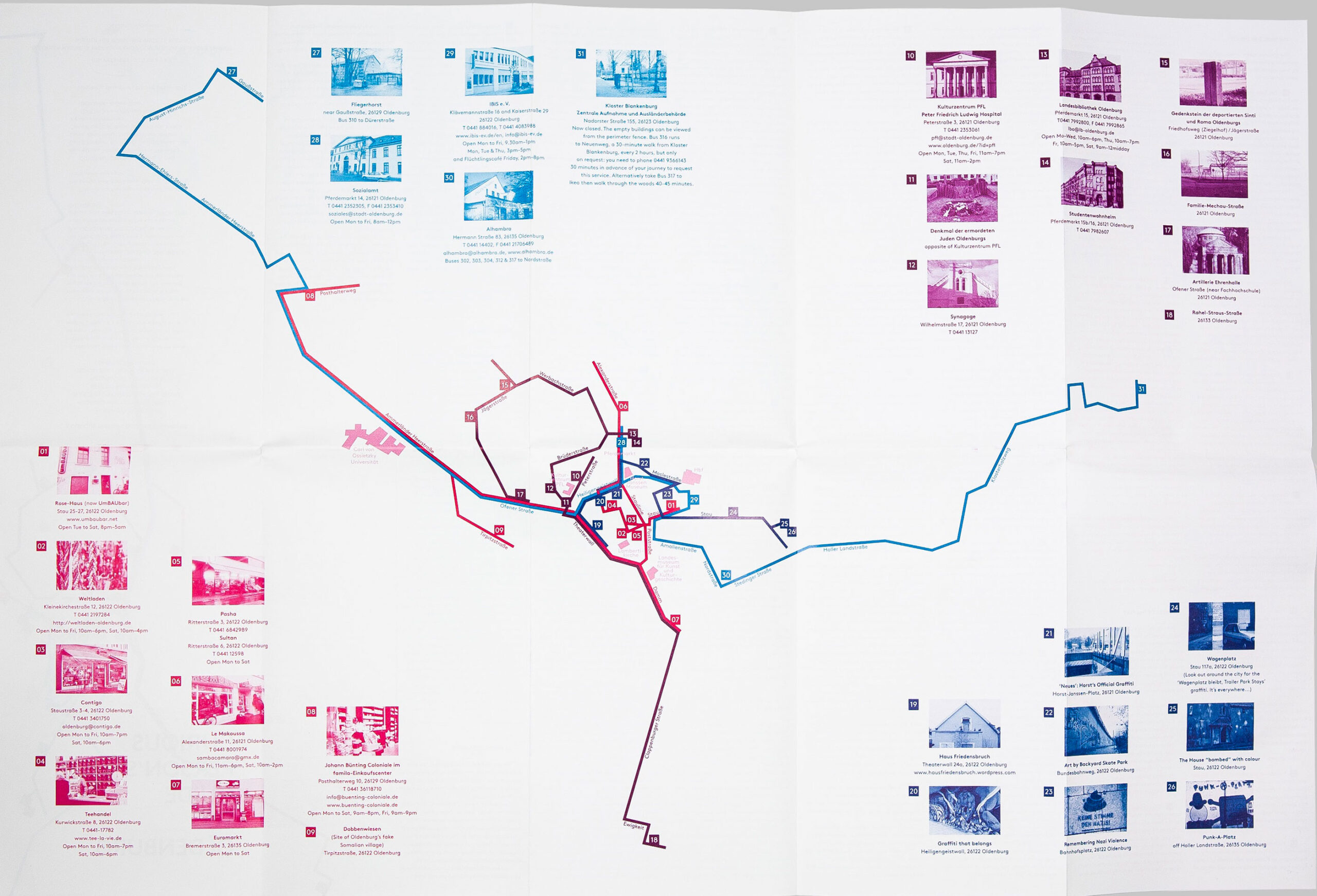

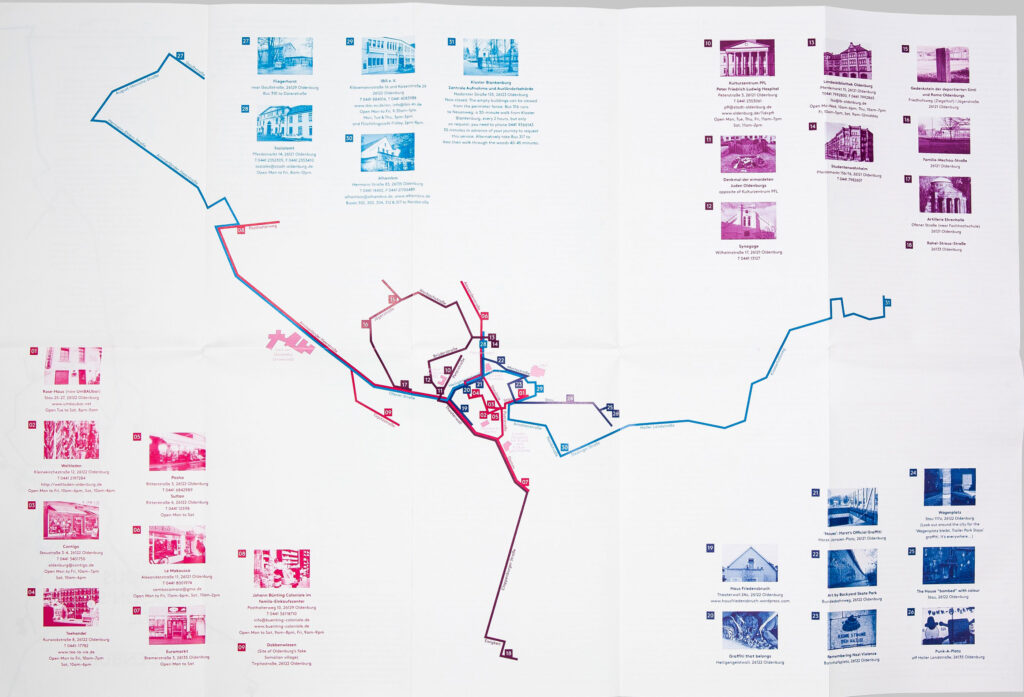

1) static maps with punctual information, such as the map produced as part of a student project “A Curious Person’s Guide to Oldenburg” (see Fig. 1).

2) interactive maps with punctual information, where users can add entries themselves (e.g. the map Topple the Racists) and/or where users can call up digitally linked elements and navigate between them (e.g. the mapping of Berlin as a postcolonial city or the web map Hamburg Global, which does not link elements on a city level, but shows Hamburg’s global connections on a nation-state level).

3)interactive maps with information on multi-perspective interdependencies, such as the map “Mapping Postcolonial” by the Munich team of [muc] münchen postkolonial, Labor k3000 and Ökumenisches Büro für Frieden und Gerechtigkeit e. V. Here, interdependencies of individual places in urban space are linked to each other through “narratives” and to structural dimensions through “layers”.

Furthermore, Sybille Bauriedl and Linda Pasch analyse the producers and addressees of postcolonial maps and find that one third of the maps analysed have a university connection and are therefore often temporary and not continuously updated. Other producers come from social movements, educational work or autonomous activist groups. The target audience is often a white majority society that needs to be informed about the colonial interdependencies of cities. However, anti-racists, decolonial activists and knowledge bearers and producers are also explicitly addressed. The question of accessibility of the maps, e.g. in municipal tourist offices or city libraries, is also important for the question of the target group.

Finally, the authors identify five challenges for combining critical and decolonial mapping. These include paying more attention to a collective process, mapping interactions between colonialism, National Socialism, Orientalism, racism and antisemitism, and linking local traces more strongly to the level of global entanglements.